We've featured the world's biggest piano stars multiple times over the years, so we thought we'd take a trip back down memory lane and feature one of our favourites: the wise, captivating Menahem Pressler

Update 06/05/2023: Menahem Pressler dies at 99. Full story here.

Interview by Erica Worth, published in 2019

A LEGEND PERSONIFIED

Menahem Pressler reflects on the renaissance of his solo career late in life, overwhelming Erica Worth for an afternoon

Pressler (second from right) after performing with the French string quartet, The Ébène Quartet, on his 90th birthday

Menahem Pressler enters the living room of his London home, and I experience a curious frisson of familiarity, even though it’s our first encounter in person. Having heard him in performance, spotted him on the back row at recitals by his friends Evgeny Kissin and Daniil Trifonov – and featured him in this magazine on many occasions – I feel as though I’ve been reunited with a long-lost uncle. But the affinity I feel runs deeper. Like me, Pressler has spent time living in the US, and like my father, he fled Nazi Germany in the late 1930s.

Pressler’s diary for 2019 is hardly that of a man in his 96th year. Inked in to August is a pair of appearances at the Oxford Piano Festival, where he has been giving recitals and masterclasses for many years: a contribution recognised in 2016 by the title of Life President of the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra. This year’s recital programme would challenge a pianist half his age. ‘I will be playing Fauré’s Sixth Barcarolle, the great Myra Hess arrangement of Bach’s Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring, then the Mozart D major Sonata – the early one, which is very beautiful’ – K311, which he proceeds to hum, gently and faultlessly.

Behind every performance lies hours of hard work. How does Pressler maintain the required stamina? ‘That depends on how you feel for the day,’ he replies. ‘It’s not as it used to be. Now I have to listen to what the body says. On certain days it’s easier, on certain days it’s more difficult.’

At this point he looks over to his partner Annabelle Weidenfeld, who is sitting with us. ‘Annabelle understands exactly how I feel and what I feel. She also knows what I should feel,’ he chuckles. ‘I always ask for her advice. It’s very important to me that she likes it. If she likes it, then I know it is good. If she doesn’t like it, then I’d better get practising! She’s critical, but critical in the most wonderful ways. That gives me confidence, and in the same time teaches me.’

Pressler & Annabelle. ©Pierre-Martin Juban

From solo to trio and back again

Living legend is an overused term, but in Pressler’s case it fits the bill. Born into a Jewish family in the German city of Magdeburg, Pressler fled in 1939 to what was then Palestine. His teachers included Leo Kestenberg, Egon Petri and Eduard Steuermann – all students of Busoni.

In 1946 his career was launched when he won the Debussy International Piano Competition in San Francisco, making his US concert debut shortly afterwards, playing Schumann with the Philadelphia Orchestra under Eugene Ormandy. During the early 50s Pressler made his first recordings, now little known, on the long-defunct MGM label: solo repertoire by Villa-Lobos and Constant Lambert, and the first recording of Debussy’s ballet La boîte à joujoux in its solo-piano form.

Only in 1955, at the ripe old age of 32, did Pressler change direction and establish the group that would be his musical home for the next half-century. The Beaux Arts Trio gave its first concert at the Tanglewood Music Festival. ‘I had a great magnificent violinist [Daniel Guilet]. He was a wonderful violinist, but an impossible person. He thought he was a Frenchman, though he came with his parents from Russia. He studied at the Paris Conservatoire and became absolutely absorbed with French culture.

The Beaux Arts Trio, 1962. From left to right: Daniel Guilet, Menahem Pressler, Bernard Greenhouse

‘And Bernard Greenhouse was one of the most beautiful cellists. The funny thing is that I grew up, so to speak, with two wonderful cellists in my life, Greenhouse and János Starker. János was on the faculty at Bloomington with me and we played some big concerts. We played the Rachmaninov Sonata… the only thing I remember from it is that his wife came in and said, “Menahem, you played too loud!” I actually listened to a recording of the performance years later, and I was thrilled. I don’t usually listen to my performances, only by accident. But here I was struck by how well I played.’

The Trio took its final bow in 2008, having performed and recorded (for Philips, now Decca) the gamut of the piano-trio repertoire, with Pressler the one permanent fixture during that time. Contented retirement would have been justly earned at that point, but Pressler has revived his solo career. ‘Simply one of the finest Mozart players of our time,’ remarked the distinguished critic Richard Freed back in 1985, and in January 2014 Pressler made a belated debut with the Berlin Philharmonic, playing the G major Concerto K453 with undimmed grace and felicity of expression. He repeated his performance at the orchestra’s New Year’s Eve concert the same year.

The Beaux Arts Trio, 2008. From left to right: Antônio Meneses, Menahem Pressler, Daniel Hope. ©Marco Borggreve

His 2019 diary includes recital appearances in Madrid and in Bochum – at the Klavier-Festival Ruhr – before his Oxford appearances. ‘We’ve already done an enormous amount of travelling,’ he tells me. ‘We had to postpone some concerts, but we’ve been in Japan, Portugal, Budapest, the Concertgebouw… it’s unbelievable.’

A lifetime of teaching and learning

1955 was a landmark year for Pressler: as well as establishing the Trio, he joined the piano faculty at Indiana University Jacobs School of Music in Bloomington, where he now enjoys the honorific title of Distinguished Professor. ‘Teaching has been important to me all my life,’ he says. ‘I have been a teacher for over 65 years. I love it.’

A lifetime of experience is distilled in his 2008 memoir and manual, Artistry in Piano Teaching (Indiana University Press), written with William Brown. ‘It has been very special for me to find out which is the best way for a particular student in a particular piece,’ he continues. ‘Every student is different – and that’s what makes it so interesting; not just interesting, but it requires your interest to be there from that minute on for that particular person.’

Pressler's 2008 memoir is available on Amazon*

Long resident in Bloomington (even if his base is in London these days), Pressler teaches there less that he used to. ‘I do have an assistant. But another professor, Asaf Zohar, who studied with me, comes over from Israel and teaches my students for two weeks at a time. He’s a wonderful teacher and enormously intense, which means he sees them not just one hour a day but sometimes for two or even three.’

From the Sorbonne in Paris, to the Gnessin Academy in Moscow, Pressler waxes lyrical about the schools of today and the talent that emerges from them. ‘So many great pianists have come out of Russia – and the one I admire a great deal is Kissin. The other is Trifonov. He came for dinner the other night after his concert with the London Symphony Orchestra and Sir Simon Rattle. It was glorious.’

Loving and listening to Debussy

An Indian summer relationship with Deutsche Grammophon has yielded albums of Beethoven and Schubert and, last year, ‘Clair de lune’, featuring Debussy, Fauré and Ravel. The title track ‘embodies Pressler’s most potent magic’ wrote one Gramophone reviewer. ‘That recording was dedicated to my girl,’ he says. ‘I made it for Annabelle. She likes French music and it was meant to show my love for her.’

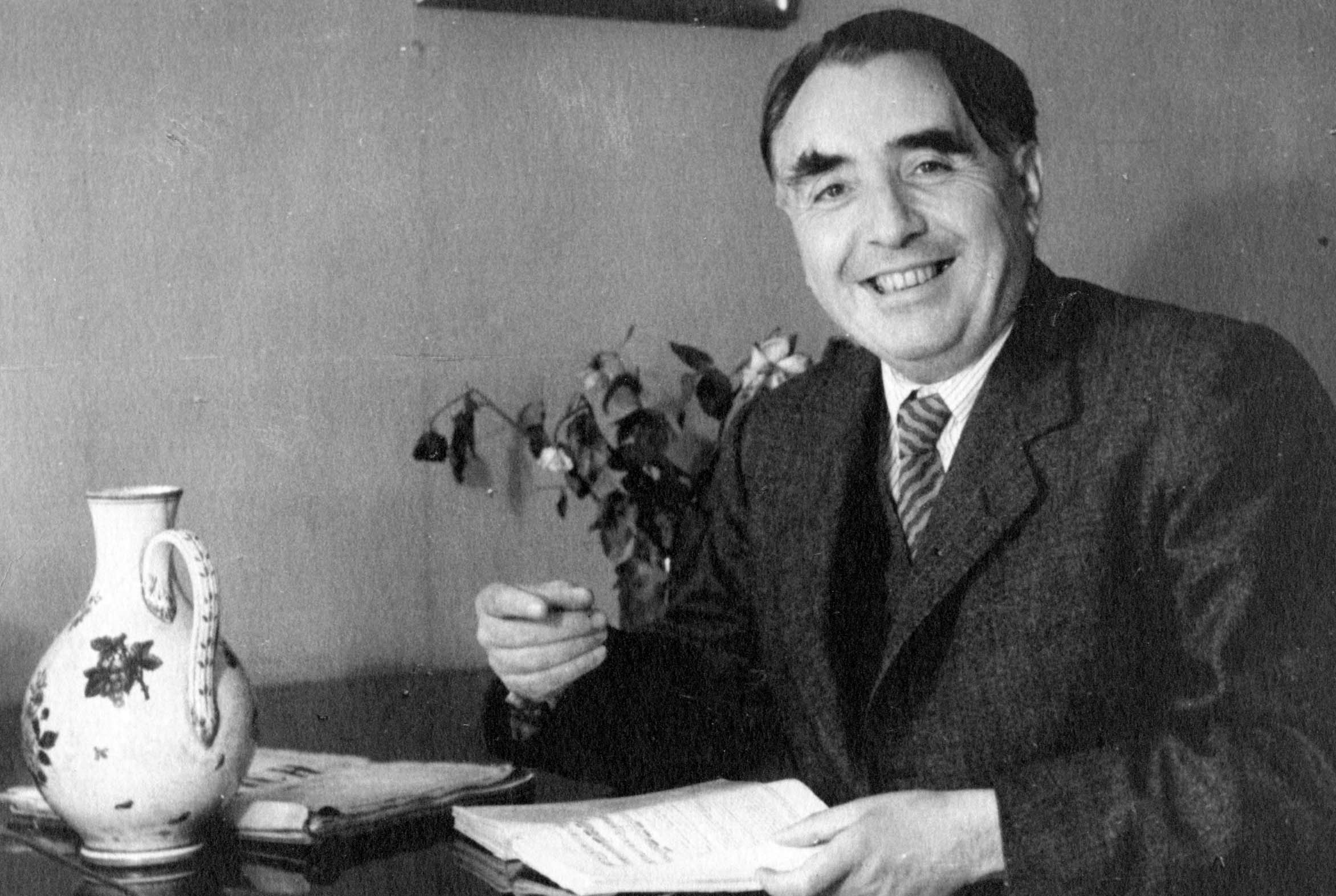

Pressler’s charm as well as his touch at the keyboard belongs to an older generation. ‘There was a famous song,’ he has recalled when thinking about the repertoire closest to him: ‘Whether they’re blonde or brunette, I love all women. And I love all music.’ The German classics – Beethoven, Bach, Brahms and Schumann – he describes as sacred. ‘Schubert is very dear to me,’ he remarks – and Mozart is placed on an even higher pedestal. But the music of Debussy – not only solo works but, of course, the piano trio – has run like a golden thread through Pressler’s career ever since his 1946 success in San Francisco. ‘A French pianist called Paul Loyonnet came to give recitals in Israel,’ he recalls.

Pianist Paul Loyonnet, 1930 ©Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

‘It was Palestine at that time, and he was such a success that the Philharmonic invited him back to play with them. He hadn’t played with an orchestra for a long time, so he needed a pianist to play the accompaniment for him – the Fifth of Beethoven and the Second of Saint-Saëns. I came to the conservatory and rehearsed with him. “That’s not bad at all,” he said. “What are your plans?” I said I’d like to go to the Debussy competition. So he asked what I played of Debussy.

‘At that time, I played Clair de lune and the two Arabesques. He said, “But that is not Debussy. Bring me tomorrow the first five Préludes and we will practise together.” He showed me how to learn Debussy, how to touch Debussy, how to listen to Debussy. I had six lessons with him which were invaluable. It would never have been possible to win without those lessons. His lessons showed me the way.’

What's his secret?

One concession to age is that Pressler attends fewer concerts. ‘When we have somebody like Kissin playing, I go. I am in love with his playing. It is uniquely beautiful. He is a special boy, a special man, in every respect. He brings the Russian tradition, which is one of the most telling ones, and he brings it to life. He has a greatness in him – even in his attitude towards his mother and his teacher.’

Kissin’s teacher is Anna Kantor, who usually travels with him on tour. She will turn 96 a few months before Pressler. What’s their secret? ‘A lot of people have problems with their hands,’ he replies. ‘Thank goodness I don’t suffer from tendonitis. I have had to endure lots of pain recently, though, and have had to go through a lot of hospital visits.’ Pressler has been in hospital these past few days, but you wouldn’t know it. ‘I have really suffered,’ he says, ‘but I came through it – and still I think about what I have done, what I could do, and what I will do.’

This drive to play, to teach, and to love and learn music more every day is Pressler’s elixir. He has been rewarded late in life with countless accolades and worldwide recognition. Magdeburg has granted him Honorary Citizenship and Bloomington has named a day after him. Pressler takes such acclaim in his stride. ‘You take the award,’ he says, ‘but it’s really for that day. You know that tomorrow is another day and you have to achieve it again. You have to be aware of it, the struggle.’

Pressler on stage with Chinese pianist Yuja Wang. © Aline Paley

We move on to lighter topics: binge-watching the Israeli TV series Shtisel on Netflix, and memories of my own teacher, Constance Keene, from New York days: ‘She played gloriously… but a tough lady!’ We exchange some pleasantries in Hebrew – mine is much rustier – and I notice that our time is soon up. ‘Goodness, we’ve been chatting for almost an hour,’ I say. ‘You see,’ he replies. ‘I overwhelmed you.’ And indeed he has done. Pressler is still a force of nature.

*As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.

Main image: © Sasha Gusov

Menahem Pressler: 1923-2023 ❤