The Slow Movement of Beethoven's 'Pathétique' Sonata Op 13 is perhaps one of the most famous sonatas in history... and it's also a piece that so many of us would love to play! Below, we show you how to play Beethoven's mighty 'Pathétique' Sonata on the piano below.

Heralding the Romantic era, Beethoven’s 'Pathétique' Sonata No 8 (written in 1798) is one of his most popular.

Unlike most of the nicknames given to Beethoven’s works, ‘Pathétique’ is believed to have been picked by the composer himself to convey its romantic and sometimes tragic mood.

Each movement conveys a different feeling: the first starts out dark and dramatic, the second is full of romance and longing, and the third is a tempestuous rondo. The outer movements require an advanced technique, but this intensely lyrical interlude – which takes the form of a song in several distinct sections – is the perfect piece for the intermediate-level pianist to learn.

This lesson will delve in to:

- Advice from Beethoven's actual students

- Why you should learn this piece in sections

- A step-by-step walk through of the central section

- Practice tips for the tricky turns in bars 20 and 21

- Where you can find the sheet music for this piece

While you're reading this article, take a listen to our recording of the piece below. We've recorded tonnes of the most loved piano pieces over the years... and this recording is certainly one of our favourites.

First up: Thoughts and suggestions from Beethoven's actual students

Ferdinand Ries claimed in 1803 in relation to this Op 13 Sonata that ‘the precision he [Beethoven] demanded is hard to believe’ and Carl Czerny advised that ‘we see from the fingering that the inner accompaniment is to be played by the right hand, without exception. The whole legato, and the melody clearly brought out. The succeeding four-part repetition of the theme, very harmonious, legatissimo, and a little louder. At the return of the theme, in the second part, the triplets very intelligible, as follows (the whole not dragging or spun out).’

Czerny also recommended a tempo of quaver equals 54 bpm, whereas Ignaz Moscheles, who prepared the piano reduction of Beethoven’s opera Fidelio under the composer’s supervision, tended to favour a quaver at 60.

Franz Liszt's advice: Learn this piece in sections

Enter Franz Liszt.

There is an account of a piano lesson given by Liszt (himself a student of Carl Czerny’s) in Paris in the early 1830s, which is relevant to this sonata. Although guiding a student through an entirely different piece, Liszt recommended getting to know the music by initially playing the outer parts, and gradually filling in the other voices. He also suggested practising accompaniment textures by themselves (meaning without any melody lines).

Liszt’s suggestion works brilliantly in the slow movement of the ‘Pathétique’. His advice is almost forensic in its impact, because you can build up an aural image of melody versus bass line, and you become aware of how many independent inner voices there are. For example, the opening bars are written in three parts, whereas bar 9 has four parts. This is echoed in the triplet textures of bar 51 (three parts) and bar 59 (four parts).

If one follows Liszt’s advice, it means learning this piece in sections. It is a quick way to get results.

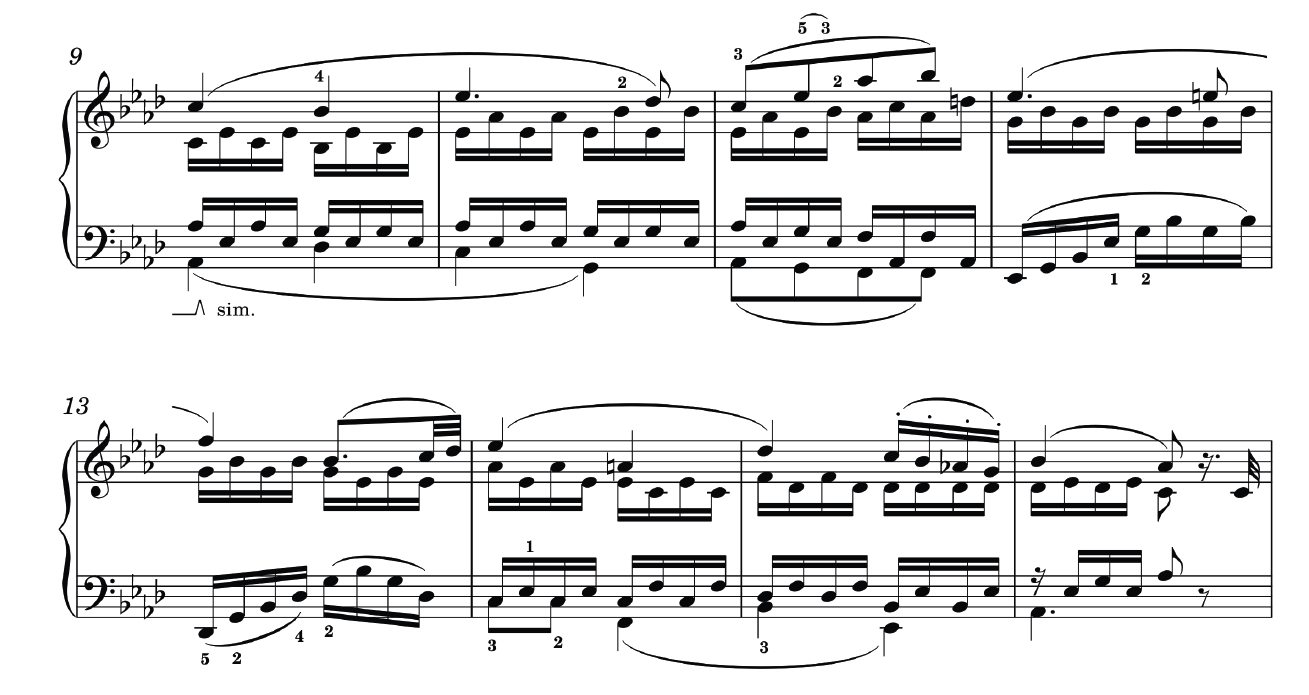

Here is another example of what I mean: once you have got used to the hand positions of bars 9-16, retaining (most of) the hand positions of bars 59-65, but changing the textures of the inner voices, is quite straightforward. Take a look below.

Bars 9-16

Bars 59-65

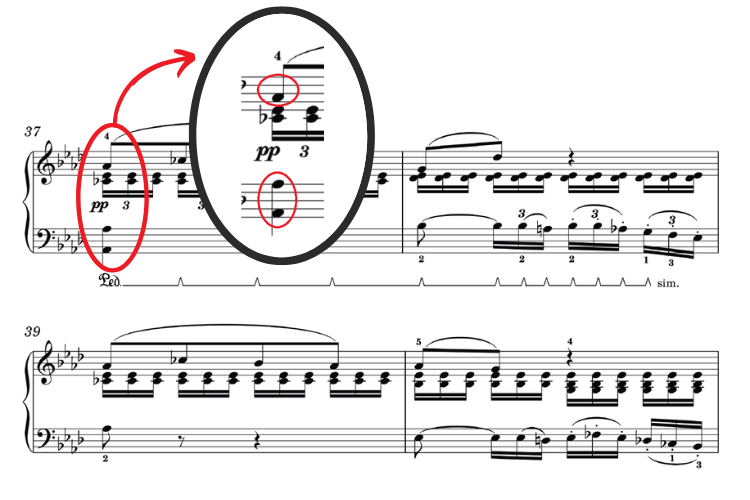

Tackling the central section (bars 37-50)

The central section (bars 37-50) anticipates the chordal textures of some of Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words. Again, ‘do a Liszt’: practise treble and bass lines only to get a feel for the melodic progressions (see above). If subsequently adding the double notes in bars 37-41 obscures the clarity of the melody line, leave out the first double note (the one that coincides with the melody line) to get a better sense of melodic clarity.

Once that feels and sounds good, add the missing double chord (the first of every group of triplets) while still retaining a clear melodic treble line. Check out our video lesson on mastering double notes if you need more advice.

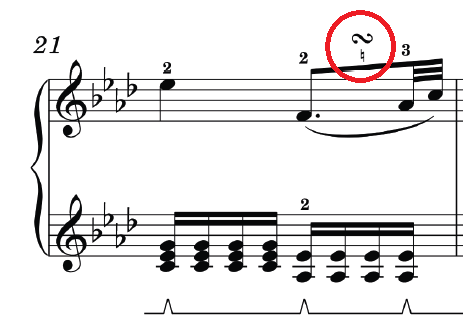

Delving into the tricky turns in bars 20 and 21

The turns in bars 20 and 21 may present some challenges, as might the beginning of bar 22.

The key to the entire passage is rhythmic consistency, so that the ornamentation sounds like an effortless enhancing of the melody line, and not like something that interrupts the rhythmic flow. So here are some practice suggestions:

1. Establish a steady, consistent flow of semiquavers by practising the chords of the LH in bars 20-23.

2. Play the initial five demisemiquavers in the RH of bar 23 as a group of notes that doesn’t end on the Bb, but leads directly into the subsequent G.

It’ll help you fit the five demisemiquavers more fluently into the available semiquaver rest.

3. The turns in bars 20 and 21 are four notes each: upper note, note, lower note, note.

To achieve an even rhythmic distribution, play all notes of the turn in bar 20 on the second semiquaver of the group in question, and align the four notes of the turn in bar 22 with the second and third semiquavers of the LH. Once it begins to sound fluent, rhythmic and effortless, you can be more flexible in the way you align the RH and LH in the turns.

Where can I find the sheet music for this piece?

The score for the Slow Movement of Beethoven's 'Pathétique' Sonata No 8 Op 13 is available right here in our sheet music store. It's just £1.99 to instantly download and keep forever.