Music educator Nigel Scaife presents an initial lesson on harmony, the basis of tonal music and a much more ‘hands-on’ music subject that’s more about the ear than the eye...

Missed part 4 of the series? View it here

Over the last two parts we’ve been looking at the various types of interval – the word used to describe the distance between two notes. We’ve discovered the ways in which these distances are named, and how a degree of either dissonance or consonance is created when two notes are sounded together. So now it’s time to start thinking about what happens when intervals are stacked up one on top of each other to create harmony, one of the most vital building blocks of tonal music.

What is harmony?

Let’s start by asking the most obvious question: what is harmony? Harmony is a word that musicians use to describe the way chords are built and the way they relate to each other within the context of a key. It refers to the vertical aspect of music, as opposed to the horizontal which is the domain of melody.

Unsurprisingly, harmony has been described in many different ways since around the start of the 17th century when the ‘common practice period’ established the basis of tonal music.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica describes it as ‘the sound of two or more notes heard simultaneously. In practice, this broad definition can also include some instances of notes sounded one after the other. If the consecutively sounded notes call to mind the notes of a familiar chord (a group of notes sounded together), the ear creates its own simultaneity in the same way that the eye perceives movement in a motion picture.’

I like music theorist and educator Steven Laitz’s definition because he relates harmony to the density of music and describes it as ‘the musical space provided by the counterpoint of two outer voices’. The composer Paul Hindemith wrote in his harmony method that ‘Harmony is a simple craft, based on a few rules of thumb derived from facts of history and acoustics – rules simple to learn and apply’. I’m not sure everyone would agree with him!

While it’s useful to know about chords – how they are created, how they are named, and how they relate to each other – this will only take the musician so far. What is far more important is that as developing pianists we should learn from practical experience how chords operate in practice, and their musical value and function in terms of their sound, colour and sonic relationships.

This is done by harmonising tunes and by improvising with chords, as well as through studying the way harmony works in the pieces being learned. So the study of harmony should be thought of as a practical ‘hands-on’ subject rather than a dry academic one. It must be more about the ear than it is about the eye.

Most of the music written in the common practice period is based on triads, which are chords made up of three distinct pitches that can be stacked up in 3rds. When the notes consist of the tonic, the 3rd and the 5th of the scale they create a chord called a tonic triad.

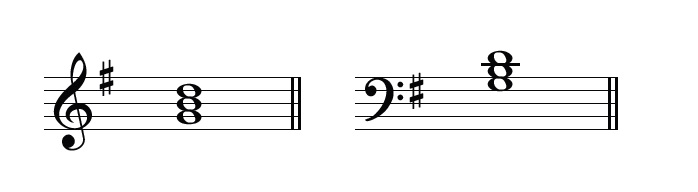

Here, for example, are tonic triads in the key of G major:

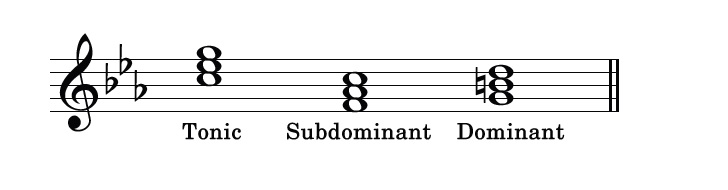

The triads built on the tonic, the subdominant and the dominant form a group called the primary triads. The primary triads in major keys are all major. Together they cover all seven notes of the major scale.

Here they are in F major:

In minor keys the triads built on the tonic and subdominant form minor chords, but the dominant triad is major. This relates to the fact that in the harmonic minor scale, the 7th degree is raised. Here are the primary triads in C minor:

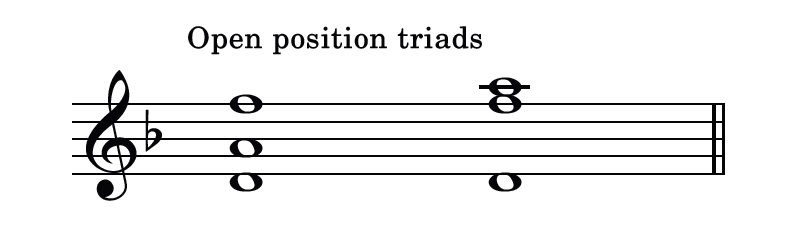

When all three notes of the triad are positioned as closely together as possible within an octave, as in the examples in the previous column, they are said to be in close position. But, of course, they can also be in different positions when the notes of the triad are spread further apart. When the notes are not confined to being next to each other within the octave they are said to be in open position.

Here is a D minor tonic triad in two different open positions:

In open position the notes might be in a different order above the tonic, as in the two examples above (i.e. D, A, F and D, F A).

Describing chords

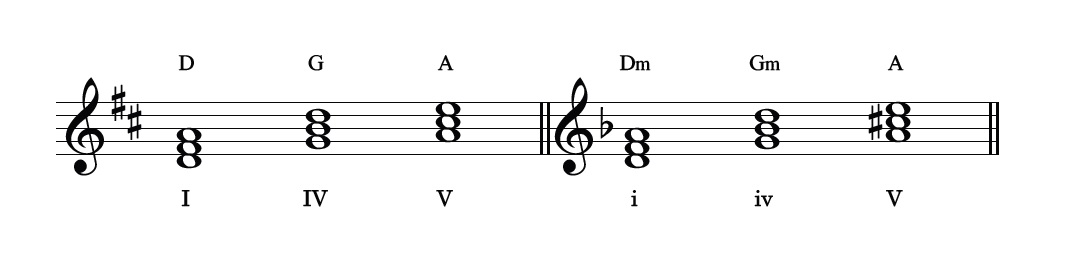

When studying harmony in classical music it is usual to consider the function of each chord in terms of its relationship to the tonic, using the scale degrees as we have done already and naming them using Roman numerals. Roman numerals are used to describe a chord when it is being written or spoken about.

These numerals are particularly useful when analysing a piece of music. When the chord is a major chord it is labelled with an upper-case symbol; when it is a minor chord it is labelled with a lower-case symbol. So the tonic and subdominant triads of a major key are labelled as I and IV, in a minor key they are i and iv. These numerals are usually placed below the bass stave.

However, in many other forms of music the chords are described simply as chords in their own right, without reference to the key in which they are appearing. In popular music and jazz styles the use of chord symbols is standard. These are placed above the stave, as you usually find in ‘lead sheets’ that give a tune and the chord symbols to identify the harmony.

With chord symbols a small ‘m’ is used to indicate a minor chord:

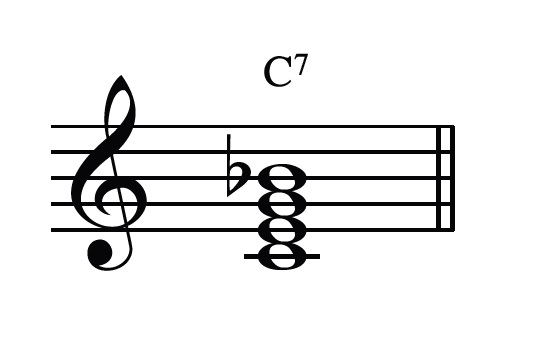

The chord symbols may also have numbers included which show additional notes to be played. The most common is the 7, which typically appears in the context of three different types of 7th chord. A single letter plus the number 7 indicates a dominant 7th chord. This chord is created when a minor 7th is added to the dominant triad in any key. In a major key this means that the additional note is the flattened leading note, sometimes called the ‘subtonic’.

In C major this note is Bb:

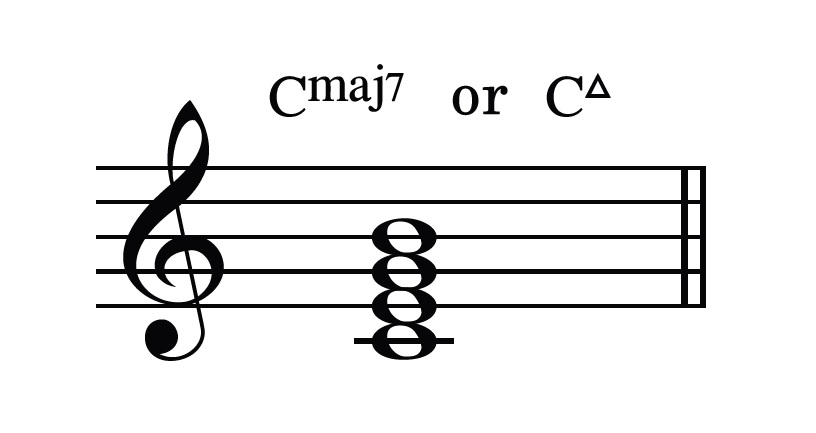

To show the chord without the 7th being flattened, which creates a major 7th chord, either a triangle sign or ‘maj 7’ is placed after the letter:

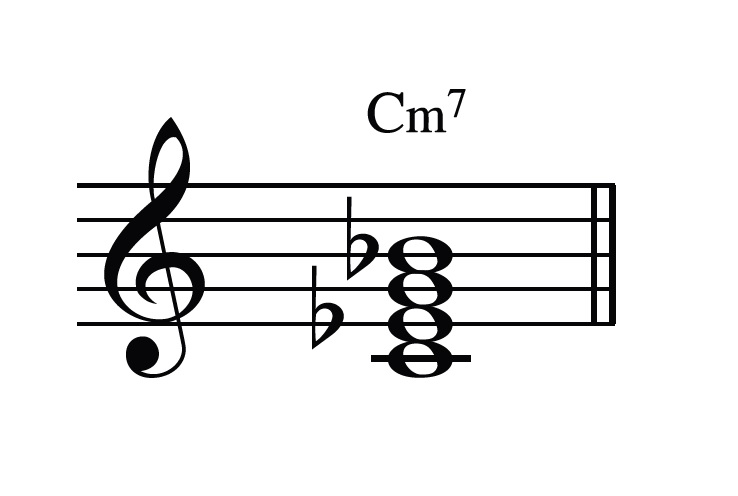

Finally, a minor 7th chord is created when a minor triad has a 7th above it:

So when discussing chord symbols it is worth remembering that ‘minor’ refers to the 3rd and ‘major’ refers to the 7th.

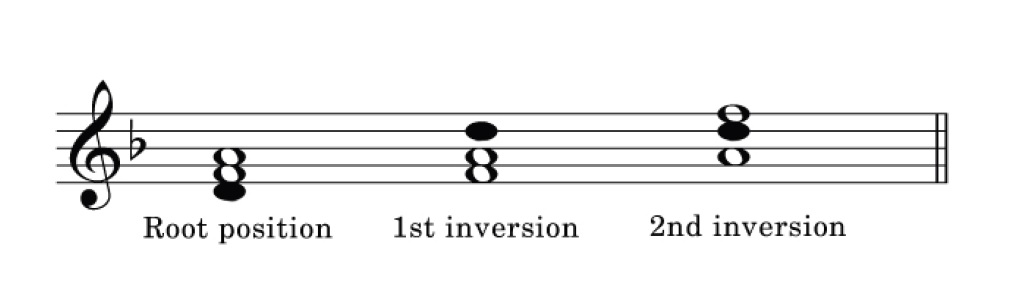

The triads we’ve covered so far have all had the tonic note, called the ‘root’, as the lowest note. These are called root position triads. However, often a chord is arranged so that the root is not the lowest note and perhaps the 3rd or the 5th is at the bottom of the texture. When the 3rd is the bass note (or lowest note) of the chord, the triad is said to be in first inversion.

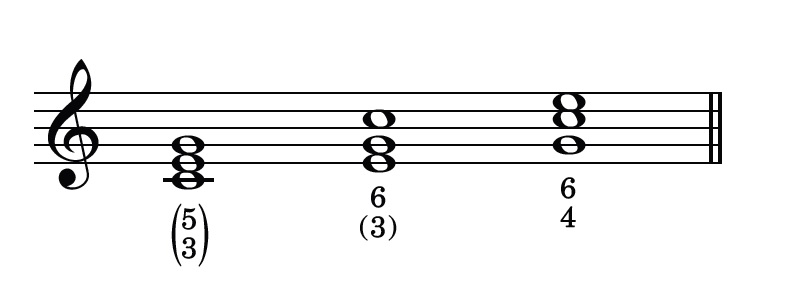

Similarly, when the 5th is the bass note, it is said to be a second inversion triad. At the top of the next column, you’ll see a D minor triad in root position, followed by its first and second inversion.

The black note heads show where the root of the chord is placed. Notice how in the inversions the root is not the same as the bass note:

When describing triads using Roman numerals, the letters a, b and c (in lower case) are used to show whether the triad is in root position or inverted. It is unusual to indicate the ‘a’, as the root position is the ‘default’ position of a chord. When describing inverted chords using chord symbols, a slash symbol – ‘/’ – is used to show how the basic chord is followed by the bass note:

Figured bass

Another way to show how a chord is constructed is through the use of figured bass, which was the standard way to indicate chords in the Baroque period. Like the use of chord symbols, figured bass does not shown the function of the chord in terms of its relationship to the key of the music, but simply indicates the chord’s construction.

This is done by counting the intervals from the bass note. For example, a root position chord may be shown as 5/3 as it consists of the tonic, with the 3rd and the 5th above. Given that root position chords are so common, the 5/3 is usually omitted and ‘taken as read’.

A first inversion chord is usually shown just as a 6, as the 3rd of the chord was again ‘taken as read’. A 6/4 chord indicates a second inversion and was written out in full to distinguish it from the 6 chord:

Keyboard players in the 17th and 18th centuries used figured bass as a shorthand for showing the chords in a similar way that jazz and pop musicians use chord symbols today.

In both forms of notation the shorthand allows the musician to improvise a part that sits comfortably within a given harmonic framework. This is usually done in the context of accompanying a singer or playing with other musicians in a band. While reading figured bass is an essential tool for the harpsichordist, today it is usual for Baroque music originally written using figured bass to have already been ‘realised’ for the pianist by an editor.

But it’s worth remembering if you’re accompanying Handel, Corelli or any similar Baroque music that didn’t have a fully notated keyboard part, you shouldn’t feel obliged to play exactly what is written but can happily go off-piste – provided it is done with an understanding of the stylistic conventions of the time, of course!

Missed previous parts of the series? Check them out below:

About the author:

Nigel Scaife began his musical life as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral. He graduated from the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Yonty Solomon, receiving a Master’s in Performance Studies. He was awarded a doctorate from Oxford University and has subsequently had wide experience as a teacher, performer and writer on music.