Music educator Nigel Scaife continues this theory series with an exploration of commonly used scales such as pentatonic and blues and a close look at modes

The first part of this series focused on major and minor scales, and considered how the construction of scales relates to keys. We saw that the major scale can be divided into two, with the upper and lower tetrachords having a direct relationship to keys which are closely related.

Looking at the various types of minor scale we discovered how the sixth and seventh degrees of the scale are often altered from the natural minor, depending on the musical context – harmonic or melodic. So now it’s time to delve into the world of other commonly used scales.

If you travel to Asia, you will be surrounded by music derived from the pentatonic scale, especially if you hear the traditional music of countries such as China and Japan, where this scale is used all the time. But you can also hear ‘pentatonicism’ in all kinds of other music such as folk, rock and jazz, as well as in Western classical music from the 18th century onwards.

A pentatonic scale has five notes within each octave. There are two types of pentatonic scale – major and minor – which relate to each other, just like the major and relative minor scales. Here is the C major pentatonic scale in the treble clef, starting and ending on C (six notes in all, as we’re going to include the C twice).

In relation to the C major scale, the two semitone-forming degrees – the fourth and the seventh – are missing, leaving minor third gaps. It is this lack of semitones that gives the scale its special character:

Here is the same scale paired with its relative minor – the A minor pentatonic scale.

The minor pentatonic scale uses the same notes but starts a minor third lower – so the gaps come in different places in relation to the starting note, A. The black notes of the keyboard are the most straightforward way for pianists to form major and minor pentatonic scales. The major pentatonic scale is often found in folk music, especially that from America, Scotland, Ireland and China. A classic example is the Scottish tune Auld Lang Syne.

The major pentatonic scale is also common in spirituals, such as Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.

The minor pentatonic is often used in rock music, especially in guitar solos, as its pattern fits easily under guitarists’ fingers. An example of an Asian melody that uses the minor pentatonic is the beautifully lyrical Love Song of Kangding. One of the most famous of all Chinese folk melodies, it was listed by UNESCO as one of the world’s top ten folk songs. Love Song of Kangding was even taken to outer space when NASA selected it as representative of the world’s most recorded songs during a satellite launch in the 1990s. You can hear Lang Lang play it with Placido Domingo and Song Zuying on YouTube, and there are many other recorded arrangements.

Because of its calming effect, the pentatonic scale is often used in music therapy. It is a good scale to use for improvisation as it is impossible to make a pentatonic tune sound dissonant with any surrounding chords, provided they are also based on the pentatonic scale.

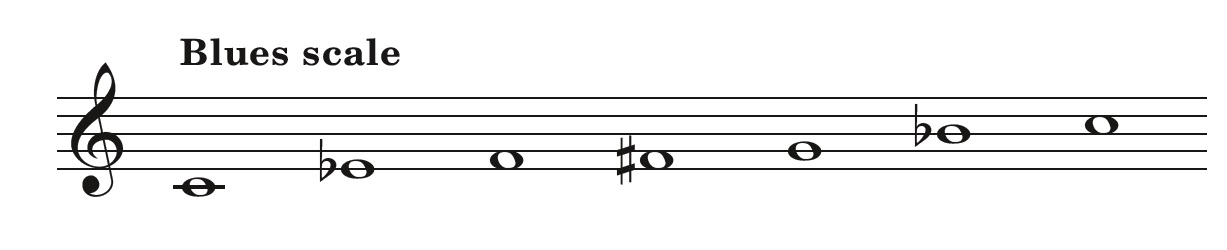

Another commonly used scale is the blues scale, which in a sense is a variant of the minor pentatonic, as it just adds one extra note – the sharpened fourth:

Because it has six pitches, the blues scale is called a hexatonic scale. Although there are different types of blues scale, the one given above is the standard version which many jazz educators use with their beginner students. This is because it can be used as a single scale which works for the whole duration of a 12-bar blues.

This can be seen if we take the chords used in a basic C blues – C7, F7 and G7 – and look at how their notes relate to the scale:

Unsurprisingly, the blues scale provides a useful starting point for exploration of the language of the blues, especially as it contains ‘blue notes’. These are the expressive notes which are often not played at the precise pitch but instead are bent, on a guitar string for example, for expressive effect. In the C blues scale the notes Eb and F# can both be

considered as blue notes which can slide to the notes a semitone above.

Modes

Music written before what is sometimes called the ‘common practice period’ (c.1600-1900) used a different set of scales to those we are familiar with today – called modes.

These scales formed the basis of the monophonic chants sung in the services of the early Christian church, the polyphonic music of the Renaissance, and folk music throughout Europe and beyond. Many classical composers in later times have drawn inspiration from modal music and the use of modes is also a common feature of contemporary jazz, folk and popular music.

We saw in the last issue that if the major scale is started on the submediant (sixth) degree of the scale, then a natural minor scale is created. In C major, this A-A natural minor scale (see below) is also known as the Aeolian mode. While major and minor tonalities can be referred to generally as ‘modes’, the term ‘mode’ is more commonly used to describe one of the modal scales that have been used since medieval times.

These scales are most readily understood as a set of scales that can be formed by playing the white notes from different starting points. It is traditional to start with the major scale and then to find the modes within in by starting a new scale on each successive note. So in this example the C major scale (presented here as the Ionian mode) can be thought of as the ‘parent scale’ from which the other six modes are extracted:

The Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian modes are known as ‘major modes’ because their tonic triads are major and they have a major quality. The Dorian, Phrygian and Aeolian modes are ‘minor modes’ because their tonic triads are minor and they have a minor quality.

The odd one out is the Locrian mode, which is known as a ‘diminished mode’. Due to its awkward structure this mode is used less often than the others.

By the mid-17th century the modal system had generally been replaced by the tonal system as we know it today, which is based around just two modes: Ionian (major) and Aeolian (minor). With the introduction of sharps and flats these scales became transposable and so led to our standard diatonic system based on minor and major tonalities.

The most commonly heard modes are the minor-sounding Dorian, used in Scarborough Fair (featured in Pianist No 87 in an arrangement by Derry Bertenshaw) and What shall we do with the drunken sailor?, and the major-sounding Mixolydian, used in the fiddle tune Old Joe Clarke and the folk song She moved through the fair. The latter was recorded by Fairport Convention in 1968 and has been recorded by dozens of artists since, including Sinéad O’Connor, a version used in the soundtrack of the film Michael Collins.

'Scarborough Fair' was featured in Pianist No 87 in an arrangement by Derry Bertenshaw

While it is useful to understand the modes theoretically in relation to C major, this approach is limited in terms of understanding the different colours and intervallic characters of each scale. To really get inside the world of modes, as jazz musicians do in order to speak the language of jazz, it is necessary to see them as distinct sounds in themselves and not just as offshoots of an existing ‘parent’ scale.

To develop fluency in this requires a lot of dedication to the art! One of the most iconic uses of modes in the jazz context is on an album by the trumpeter Miles Davis. There’s no better place to discover the world of modal jazz than Kind of Blue, thought to be the best-selling jazz album of all time.

The track ‘So What’, for example, is based on two Dorian scales, the first on D and the second on Eb. It is also a notable tune for its use of ‘quartal harmony’ – that is chords made up of fourths, which you can hear played by Bill Evans as the ‘So What’ chords at the start. Well worth exploring if you are new to jazz.

Other common scales

As its name suggests, the whole-tone scale is built from notes which are a whole tone apart, dividing the octave into six equal steps. There are only two whole-tone scales:

As there are no perfect fourths or fifths in this scale it is not possible to create common chords from its pitches. It is this lack of tonality that gives the scale its mysterious and dream-like quality. Among composers who have used the whole-tone scale are Glinka, Liszt and Vaughan Williams.

However, the composer most associated with its use is undoubtedly Debussy. His wonderfully evocative Prélude Voiles (‘Veils’ or ‘Sails’), composed in 1909, is a celebrated example. Here is the opening:

The octatonic scale is theoretically any eight-note scale. However, the term is usually used to describe a symmetrical scale containing alternating intervals of a tone and a semitone, such as this:

Because it has such a complex mixture of pitches which allow for a wide variety of chords to be produced, it can be used to create a sense of bitonality – the simultaneous combination of two keys. The octatonic scale was used in the late 19th century by Liszt and particularly by Russian composers such as Glinka, Rimsky-Korsakov and Scriabin.

It became an important organisational device in 20th-century music and is found in music by Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Bartók and Messiaen. It’s not an easy scale to identify in terms of hearing when it is being used, as it tends to be more of a compositional tool than something which is immediately recognisable aurally.

To explore it at the piano, take a look at the musical example below:

This is the opening of No 109 from Bartók’s Mikrokosmos (Book 4), which he called ‘From the Island of Bali’ and is evocative of the Balinese gamelan.

Nigel Scaife continues the series in Part 3, which you can view here.

About the author:

Nigel Scaife began his musical life as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral. He graduated from the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Yonty Solomon, receiving a Master’s in Performance Studies. He was awarded a doctorate from Oxford University and has subsequently had wide experience as a teacher, performer and writer on music.