In the final part of the series, Nigel Scaife gets to grips with the materials and construction of well-ordered counterpoint

In the first instalment of our anatomy of Fugue, we looked at its core features, taking for an example a fugal episode in the finale of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto.

During the course of this movement the Rondo theme played by the soloist at the start is taken as the basis for a fugal subject played by the cellos. The full orchestral texture is unexpectedly reduced to a single part, which alerts us as listeners to the possibility of this idea forming the subject of a fugue.

Once the cellos have played the subject it is followed by what is known as an answer – the same musical idea played a fifth higher by the second violins. The cellos continue with a countersubject resulting in two-part counterpoint. Then the fugue subject reappears as the contrapuntal texture thickens – and on it goes. This Beethoven example served to show how a fugue is a contrapuntal piece which has each part, or ‘voice’, entering successively, with the same musical material being transferred from one part to another, albeit at different pitches.

This compositional technique is called imitative counterpoint.

The origins of fugue

The most straightforward example of music based on imitative counterpoint is a canon.

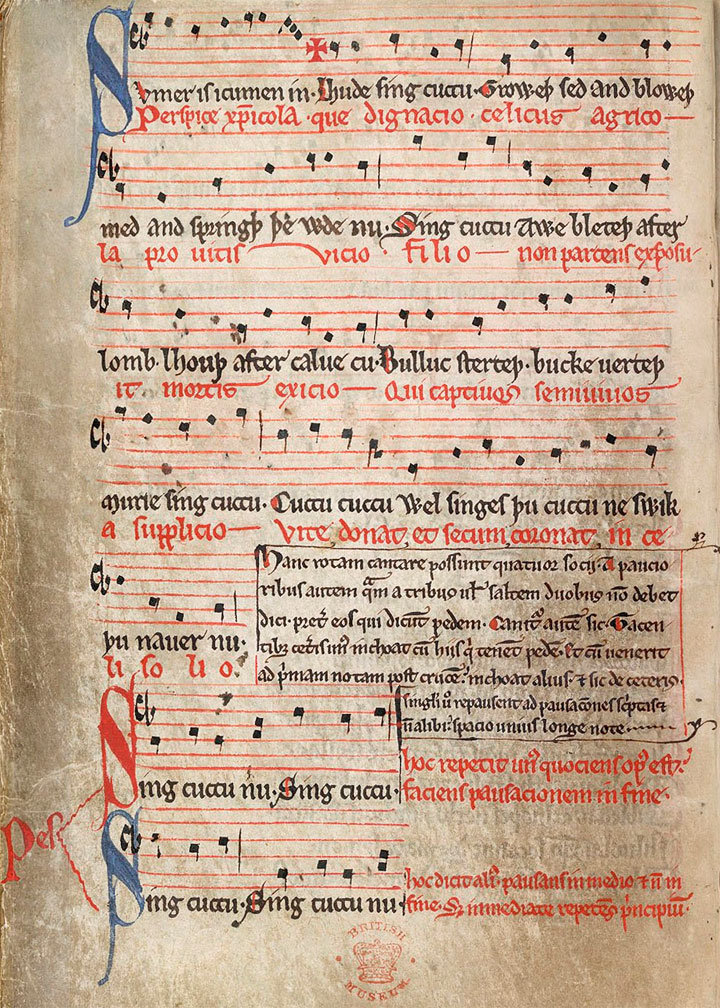

In a canon, the tune is imitated at a specified time interval by one or more parts at the same pitch. The oldest known canon and one of the most famous is a 13th-century secular song, Sumer is icumen in, a beautiful manuscript of which can be seen at the British Museum.

An image of the 'Sumer is icumen' in manuscript

Simple repeating canons in which each voice has identical musical material are called rounds: Three Blind Mice and Frère Jacques are classic examples.

Pieces using this kind of strict imitation were called fuga in the 14th century, but it later became more common to differentiate canon from a freer use of imitative counterpoint. In a canon the theme becomes virtually lost as a strand of melody once all voices have entered and the texture is uniform, whereas in a fugue strict repetition is not maintained and there is more creative freedom for the composer within the restrictions of the genre. This opens up all the multifarious expressive elements that we hear in fugues, whereas canons are much more constrained and have a limited set of creative possibilities.

The element of imitative counterpoint is the link between fugue and its precursors, as its origins can be found not just in canons but in the ‘points’ of imitation which Renaissance and early Baroque composers used in their motets and other vocal pieces, as well as in keyboard toccatas, ricercars and fantasias. These melodic ideas are often little more than a formula of notes, quite brief, with the purpose of building up a polyphonic texture, but Baroque-era composers used ever longer melodic ideas to develop themes in an imitative style.

The power of fifths

Crucially, it became necessary for a fugue, as opposed to other types of piece based on imitative counterpoint, to have parts that enter at the intervallic distance of a perfect fifth, perfect fourth or octave to each other at the start. Why? Because only at these intervals can the thematic identity of the subject be preserved within the same diatonic scale.

So, for example, if a theme is based around the notes of the tonic triad in C major (C, E and G), these can be imitated within the C major scale by F, A and C or G, B and D. At other positions either the mode changes from major to minor or notes which are foreign to C major have to be introduced.

The preference for imitation at the distance of a fifth higher or a fourth lower was due both to the increased variety that these intervals provided and to the fact that they accommodate the natural compass of human voices from soprano to bass.

This was also a practical solution for fugues written for keyboard instruments as these distances conveniently accommodate the stretch of the player’s hands.

Bach’s C minor Fugue

To delve deeper into the nature of fugue, let’s turn our attention to a specific example – a fugue in C minor BWV847 by JS Bach, No 2 in the First Book of The Well-Tempered Clavier. This particular fugue has been used over many generations as a paradigm for analysing how fugues work. Its exemplary status has come about because it isn’t too

complex and it provides a vehicle for introducing many of the essential terms used to describe fundamental features of the form.

The Fugue in C minor is in three voices – soprano, alto and bass. A three-part texture is common in The Well-Tempered Clavier, but of course there are many fugues with more than three parts. The independence of each part is maintained until the last couple of bars or so, when the piece is brought to a conclusion with a tonic pedal and chords are introduced to add richness to the texture and to round it off conclusively. Here the subject is first stated by the alto, followed by the answer in the soprano, with the alto’s countersubject underneath.

Note that the subject starts on the tonic and that the dominant is strongly presented as the first note of the second bar, with the third of the tonic triad being the note that the subject ends on: we can be in no doubt about the tonality here!

Opening on an upbeat lends to the fugue a rhythmic lightness, and in turn a sense of momentum. Bach is far too much the master of his art to compose a four-square fugue subject: rhythmic propulsion and fluidity are hallmarks of his contrapuntal writing.

The answer is a tonal answer (as opposed to a ‘real’ answer), as the first G of the subject (the dominant) becomes the tonic note in the answer in order to maintain the tonality, rather being an exact transposition of the subject. The combination of answer and countersubject is designed to be ‘invertible’ – that is, either part can be used as the lowest part without breaking the conventions that concern the treatment of dissonance. These conventions can be a little confusing at first, but in a nutshell the interval of a fifth is consonant, whereas when it is inverted, the fourth is treated as a dissonance when it occurs in the lowest part.

The countersubject starts with a descending scale, which is a feature that will be heard throughout the piece. Not all fugues have a countersubject as some present counterpoint alongside the answer that doesn’t then recur later in the piece. Where the material does return as a regular feature it often has a subsidiary quality which is distinctive without detracting attention away from the subject. For example, the character of a countersubject may be determined by a tied note, a suspension or some particular rhythmic feature.

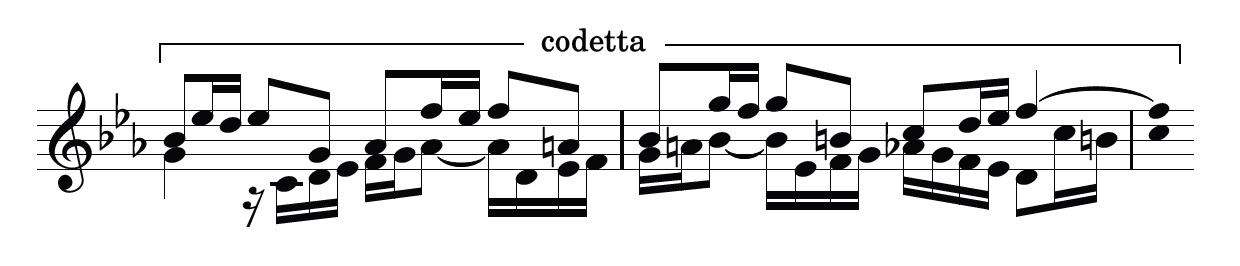

Following the statement of the answer and countersubject, finishing at the start of bar 5, there is a continuation of counterpoint for two bars until the final voice enters. A fragment of the subject is treated in sequence by the soprano while the alto has a scalic figure which relates to the countersubject, although now in contrary motion:

Such a passage is commonly called a codetta. This term is used in a specific way in the context of fugue and shouldn’t be confused with its more general meaning. By analogy with sonata form it suggests some kind of cadential rounding off, whereas in fugue it is the opposite of a cadence as it forms a linking passage between fugal entries. I have to agree with Roger Bullivant, who wrote in his excellent book on fugue that the term is ‘one of the silliest in conventional fugal theory’.

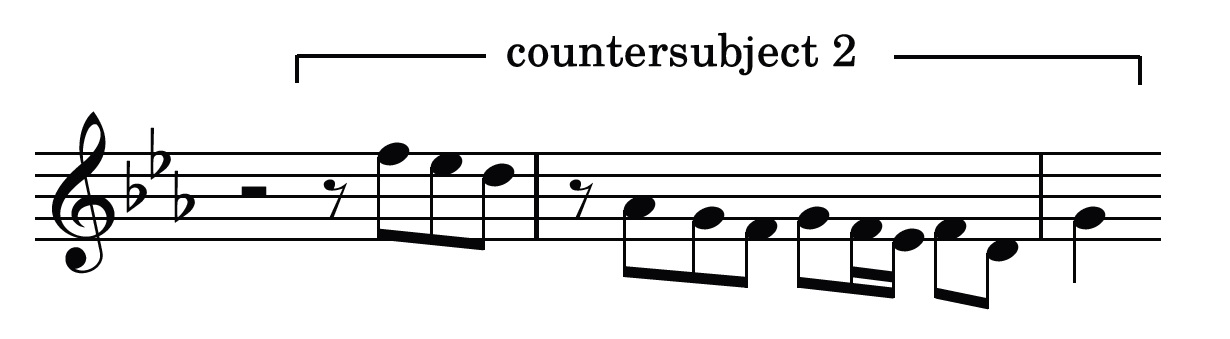

The third voice – the bass – enters at bar 7 with the subject in its original form accompanied by the countersubject in the soprano. There is then a second countersubject in the alto part which is an idea treated quite freely throughout the fugue.

In his written introduction to this fugue (in an edition published by ABRSM), Sir Donald Tovey offers some words of wisdom which have relevance to the performance of all fugues: ‘The two Countersubjects demand as much attention as the Subject, with which they form a Triple Counterpoint which appears in five of the six possible permutations…. The combination of all three sounds quite clear with an evenly balanced tone, and the effort of the pianist should not be to “bring out” this or that theme, but to keep the phrasing of each independent.’

The statement of the subject by the final voice in the fugue marks the end of the Fugal Exposition. In a fugal exposition each voice enters in turn with the subject, in either subject or answer form, usually with the entries alternating between subject and answer statements. However, there are exceptions, as always! For example, the first fugue in Book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier has the sequence of subject – answer – answer – subject. Nevertheless, it is true to say that the exposition is the most strictly regulated part of a fugue.

So what happens next? After the exposition in a fugue there will usually be an alternation between statements of the subject and material which is freer. The freer material, which does not contain a complete statement of the subject but which forms a gap between statements, is called an episode. Not all fugues have episodes – the opening C major fugue of The Well-Tempered Clavier is a good example, where the entire piece is built from entries of the subject – but most do, as without them the music runs the risk of becoming too intense.

Episodes can provide musical breathing spaces and a means of modulating and preparing the way for a statement of the subject in a new key.

Missed previous parts of the series? Check them out below:

About the author:

Nigel Scaife began his musical life as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral. He graduated from the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Yonty Solomon, receiving a Master’s in Performance Studies. He was awarded a doctorate from Oxford University and has subsequently had wide experience as a teacher, performer and writer on music.

*As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases.