Music educator Nigel Scaife guides us through a series on theory with a look at the most commonly used major and minor scales – and considers how they relate to each other

Scales are one of the basic building blocks of music. Knowing your scales as a musician is a bit like knowing your times tables as a mathematician – they are an essential tool without which fluency is impossible.

For pianists, this ‘knowing’ of scales is usually both a technical consideration in practising the shapes and finger patterns in order to develop technique – evenness, rapidity, and so on – and a more cerebral one in terms of knowing how scales are constructed and how they relate to each other within the tonal system.

There are many different scales to consider – not just major and minor, but pentatonic, whole tone and octatonic – and we’ll be taking a look at modes as well!

Unlike players of woodwind, brass or stringed instruments, we pianists are fortunate in having the keyboard as a visual guide to help us understand how scales work. We can see at a glance that the octave divides into 12 pitches, each of which is equidistant from the next by a semitone. Playing each note ascending to make a chromatic scale using all 12 pitches is a bit like going up and down a series of steps and it is this feature that gives us the word ‘scale’ – from the Latin scala, meaning a ladder or staircase.

Back in Medieval and Renaissance times musicians used a set of scales called ‘modes’ – something I’ll touch on in the next issue. But since the Baroque period, classical music has largely been written in one of two basic modes: major and minor. Both of these types of scale use a mixture of tones and semitones, and it is this combination of intervals that gives each type of scale its distinctive character.

A piece based on a scale is said to be in a specific key or tonality. Tonality can be loosely described as the organisation of pitches around a central tonic in a piece of music. The notes contained within the scale are called diatonic – from the Greek word meaning ‘through the tones’. Other pitches that lie outside of the scale, and which therefore require an accidental, are called chromatic – a word taken from the Latin chroma for colour.

The major scale

Let’s start by looking at the way the major scale is constructed, because understanding this unlocks the way keys relate to each other – something that is of fundamental importance to knowing how tonal music works.

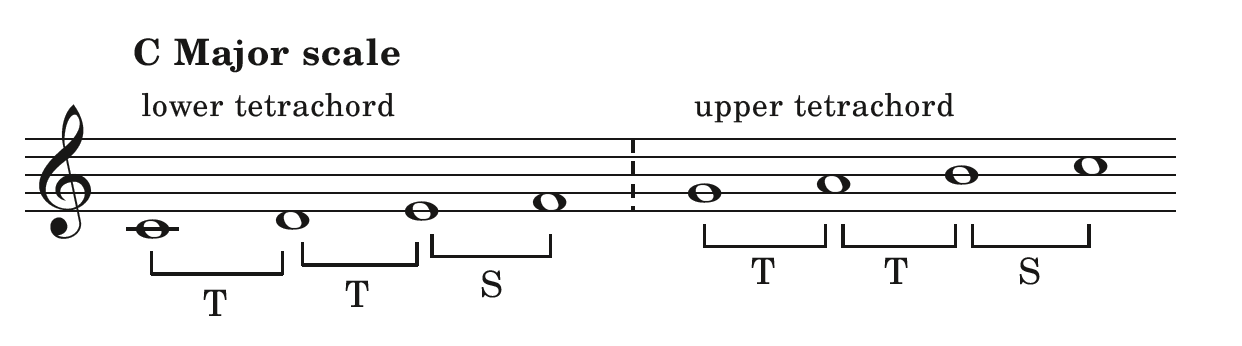

Each major scale can be divided into two groups of four notes, each of which has the same combination of intervals: a tone (T) followed by another tone and then a semitone (S). Between the two groups of four notes there is the interval of a tone. These two series of notes are called tetrachords:

The lower tetrachord of C major is the same as the upper tetrachord of F major, while the upper tetrachord forms the start of the G major scale:

So within the structure of the C major scale we can see that there is a direct relationship with two other scales – F major (using one flat) and G major (using one sharp). This is the basis of the circle of fifths pattern of keys which will be covered in a later article.

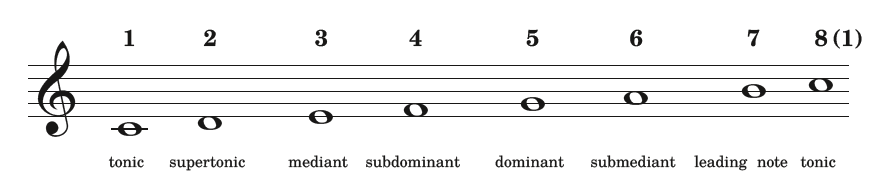

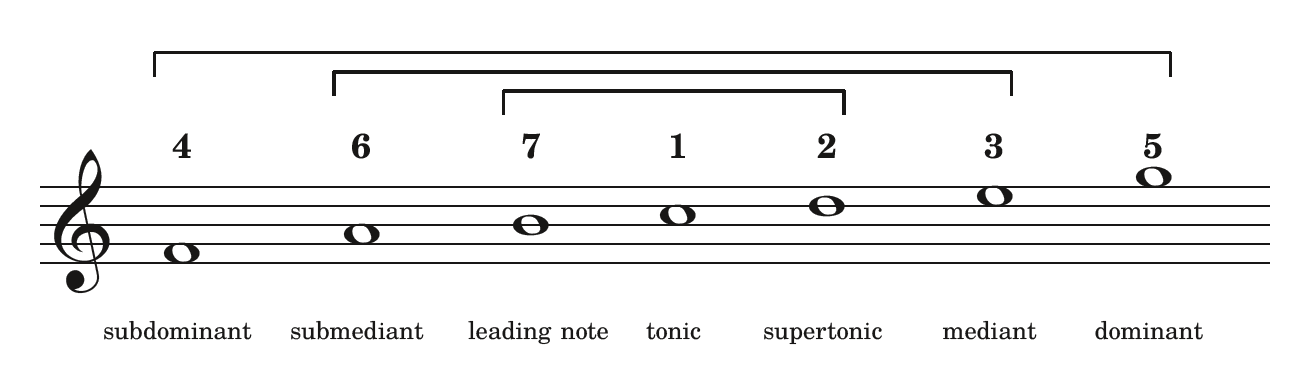

Each degree of the scale has its own name:

It’s worth mentioning that the subdominant should be thought of as the ‘under dominant’, being five notes of the scale below the tonic. Similarly, while the mediant is the third note above the tonic, the submediant is three notes below.

By placing the tonic in the middle and arranging the notes around it, this symmetrical pattern becomes clear:

There’s a hierarchy of importance with these scale degrees, as there is with the chords that are built on them, with the tonic being by far the most important note of all.

The tonic is like a centre of gravity: it defines the key and all other notes are subordinate to it. The second most important degree after the tonic is the dominant, followed by the subdominant.

It is worth noting that the two scales that contain the lower and upper tetrachords of the C major scale respectively – F major and G major – are those built on the subdominant and dominant degrees of the scale.

Triads built on these three degrees are known as the primary triads and are often labelled using Roman numerals: I (tonic), IV (subdominant) and V (dominant). (I’ll be discussing triads in a future article.)

The minor scale

There are three types of minor scale: natural, harmonic and melodic. Each of them is differentiated from the major scale mainly because the third scale degree is a semitone lower than in the major scale. The sixth and seventh

degrees are more variable in the minor mode, as we’ll see when we explore each different type of minor scale in turn.

The natural minor scale is the basic, plain minor scale and is perhaps the oldest form of the minor mode. It contains the same notes as its ‘parent’ major scale, but starting on the submediant. So if you play the white notes of the piano from A (the submediant in C major) to A you are playing the natural minor scale that relates to C major:

Because of this close relationship with C major, A minor is called the relative minor scale of C major – which in turn is the relative major of A minor.

By thinking down any major scale until you get to the submediant (i.e. a minor third below the tonic) you will always get to the relative minor key which will share the same key signature. For example, taking F major with its one flat key signature and thinking down to the submediant you arrive at D. So the relative minor key of F major is D minor – both keys sharing the same key signature of one flat: B flat. The natural minor scale is more often found in popular music, folk and jazz than it is in classical music (e.g. Van Morrison’s Moondance, the Gypsy Kings’ Bamboleo, Simon and Garfunkel’s The Sound of Silence and the carol God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen).

There are some well-known classical examples such as Tchaikovsky’s Old French Song. The tune Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem, also uses the natural minor, as does the folksong Poor Wayfaring Stranger – a song about the journey through life that was made famous by Jack White on the soundtrack to the movie Cold Mountain.

The natural minors starting on A, E and D all have the same fingering as C major, so are a really easy starting point for playing.

The harmonic minor scale differs from the natural minor through having a raised seventh both ascending and descending. It is called ‘harmonic’ because it is the scale that is usually referred to when dealing with harmony in minor keys. The reason for that is because it includes the notes of the three ‘primary triads’ – those built on the tonic, subdominant, and dominant (with raised third, making it a major triad) – in the minor key:

The melodic minor has the sixth and seventh degrees raised from the natural minor on the way up, but is the same as the natural minor on the way down.

This scale is named ‘melodic’ because it references the typical movement of minor key melodies where the raised seventh acts as a leading note in the ascending direction and has a natural ‘pull’ up to the tonic. The sixth is also raised as a consequence, to avoid an awkward interval between the sixth and seventh degrees and to make the melodic line smoother.

On the way down the scale reverts to the natural minor:

In reality, none of these minor scales gives us a complete picture of how the minor mode operates in actual music, as in a sense they are abstractions.

But by being aware of them and being able to think about them collectively, we can gain a deeper understanding of how pieces in minor keys operate.

Nigel Scaife continues the series in part 2, available here.

About the author:

Nigel Scaife began his musical life as a chorister at Exeter Cathedral. He graduated from the Royal College of Music, where he studied with Yonty Solomon, receiving a Master’s in Performance Studies. He was awarded a doctorate from Oxford University and has subsequently had wide experience as a teacher, performer and writer on music.