Writer Philip Clark, author of Brubeck’s biography A Life in Time takes us on a moving journey through the life and music of this pioneering composer and pianist

At the end of 1967, Dave Brubeck disbanded his famous quartet.

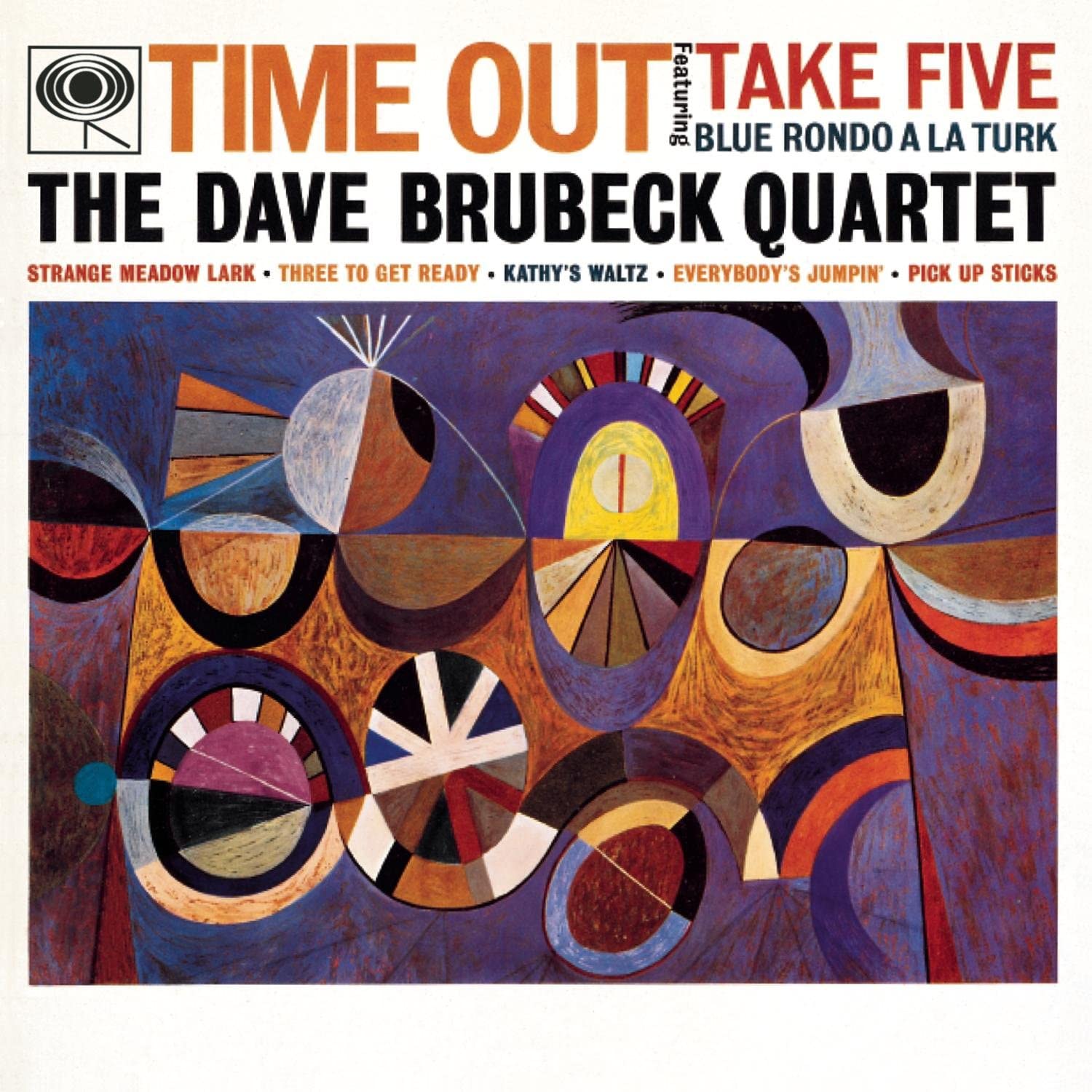

Ever since 1958, when the group’s line-up stabilised around Brubeck (piano), Paul Desmond (alto saxophone), Eugene Wright (bass) and Joe Morello (drums), the ‘classic’ Dave Brubeck Quartet had been an essential part of the modern jazz landscape. Brubeck’s 1959 album Time Out, in which he presented the first versions of ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk’ and ‘Take Five’, took instrumental jazz to the pop charts for the first time since the 1930s, when the likes of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw had been the pop stars of their day. Brubeck disbanded the group because quitting while he was ahead seemed sensible, but also because he wanted to devote his creative energies to writing choral and orchestral music.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet's 1959 release, Time Out

That aspiration, however, did not last long. Within a few months he had hit the road again with a brand-new quartet featuring another star saxophonist, Gerry Mulligan. Brubeck would then spend the rest of his life touring – playing his final concerts only 18 months before he died on 5 December 2012, the day before his 92nd birthday.

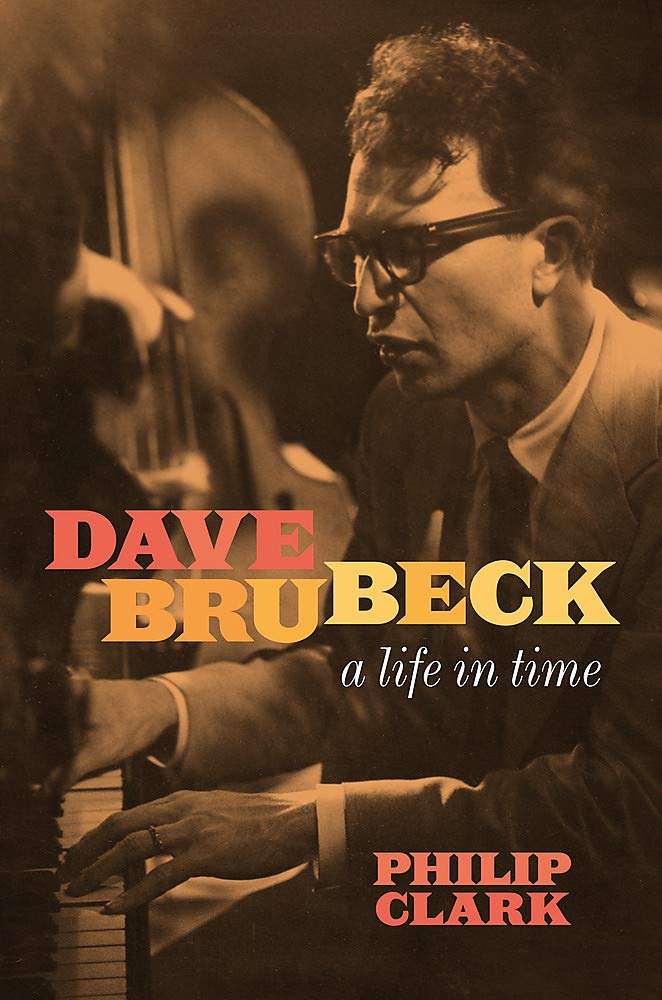

Why would anybody want to write a jazz biography? The hours are long and hard and the economics are stacked against you, but in the end I found not writing my recently published biography Dave Brubeck: A Life In Time more of a problem than sitting down to begin.

Dave Brubeck: A Life In Time – by Philip Clark

Since I became a music journalist in 1999, Brubeck’s music had represented a personal crusade. The very first piece of journalism I published, in the now defunct Classic CD magazine, had been an interview with Brubeck. By that point he was almost 80 and an icon of jazz and American music, the last survivor of a golden era of modern jazz. Miles, Coltrane and Monk had all gone, but Dave was still delivering jazz, hot and creative. And audiences were flocking to his concerts.

He certainly didn’t need a champion – and yet it bothered me that the soar-away success of Time Out and 'Take Five' had blocked the light on so many of his wider achievements. Time Out didn’t come from nowhere. Brubeck’s first recorded statements were made 13 years earlier in 1946 – but also endlessly fascinating were those questions of how Brubeck dealt with the aftermath of Time Out’s success, pumping tunes like ‘Take Five’ and ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk’ with creative energy for the next 40 years.

The Brubeck Effect

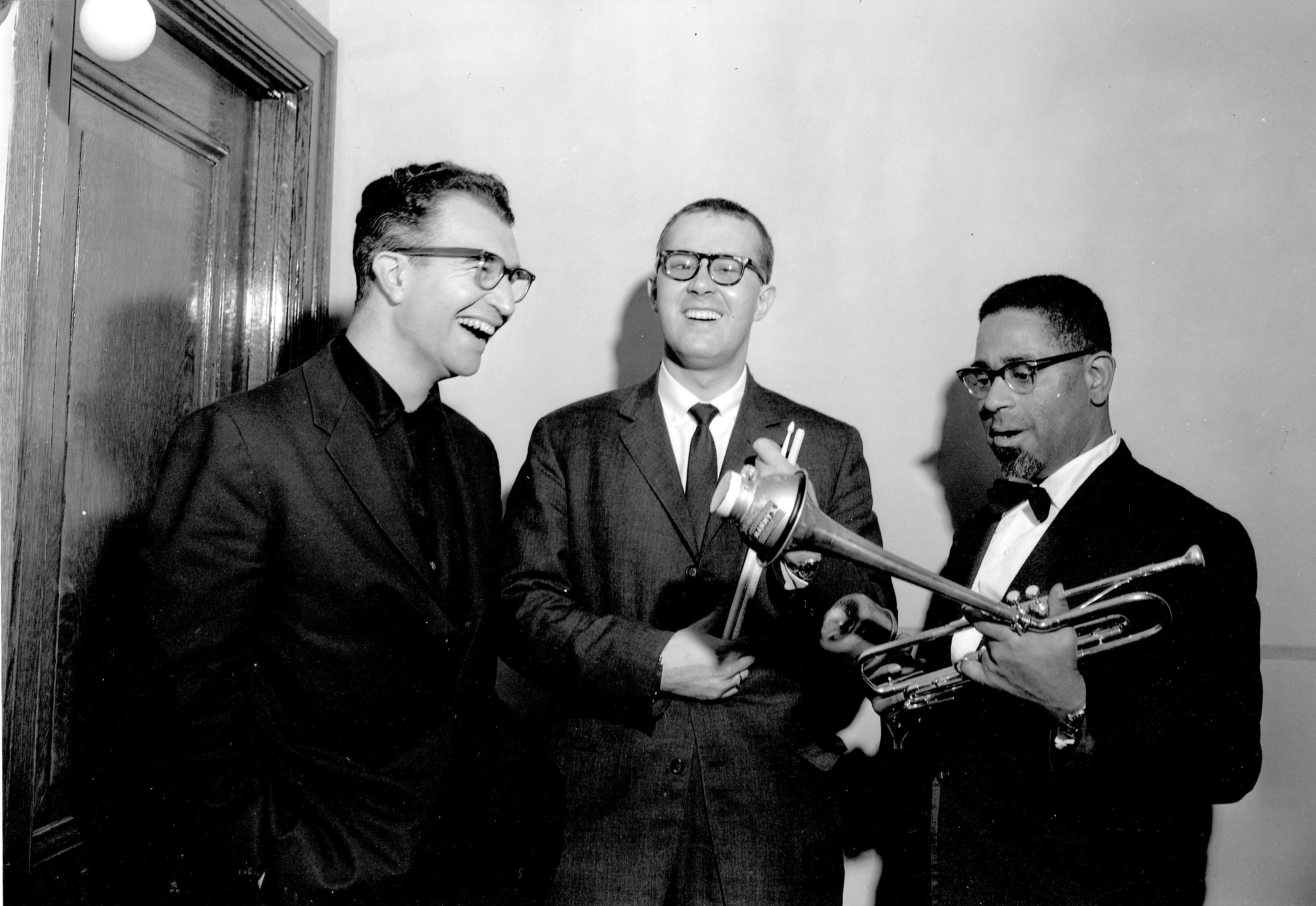

Brubeck (left) with Joe Morello and Dizzy Gillespie (c.1959)

This mattered to me because, without Brubeck, I might not have had a life in music at all. During my early childhood my dad, who is a painter, listened to Time Out on a loop while he worked. Family mythology insists that whenever ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk’ started, I would run into his studio screaming with joy and dancing to the music. That was my introduction to jazz.

Then, in my early teens, Brubeck changed my idea of music once again. During a family holiday to Spain, in a second-hand record shop in Figueres, I found a cassette of a 1973 Brubeck album, We’re All Together Again For The First Time, so called because Brubeck had invited Paul Desmond to guest with the new quartet featuring Gerry Mulligan. As my dad drove out of the city into the boiling Mediterranean heat, I loaded the cassette up to play – and what I heard rearranged the molecules of my brain.

The opening track, ‘Truth’, wrapped a punky melodic line around a relentlessly spinning riff that, without warning, plunged into a breakout of atonal fury. Brubeck’s improvised solo reflected the harmonic tensions embedded inside his composition by establishing a propulsive groove that he proceeded to shatter with ricocheting clusters of hammered notes and spiky, atonal ribbons of dense counterpoint. Within a week I was listening to totemic albums of the jazz avant-garde like John Coltrane’s Ascension and Cecil Taylor’s Unit Structures; and music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Charles Ives and Edgard Varèse. Clearly, Brubeck was more than just the ‘Take Five’ man.

Destination Jazz

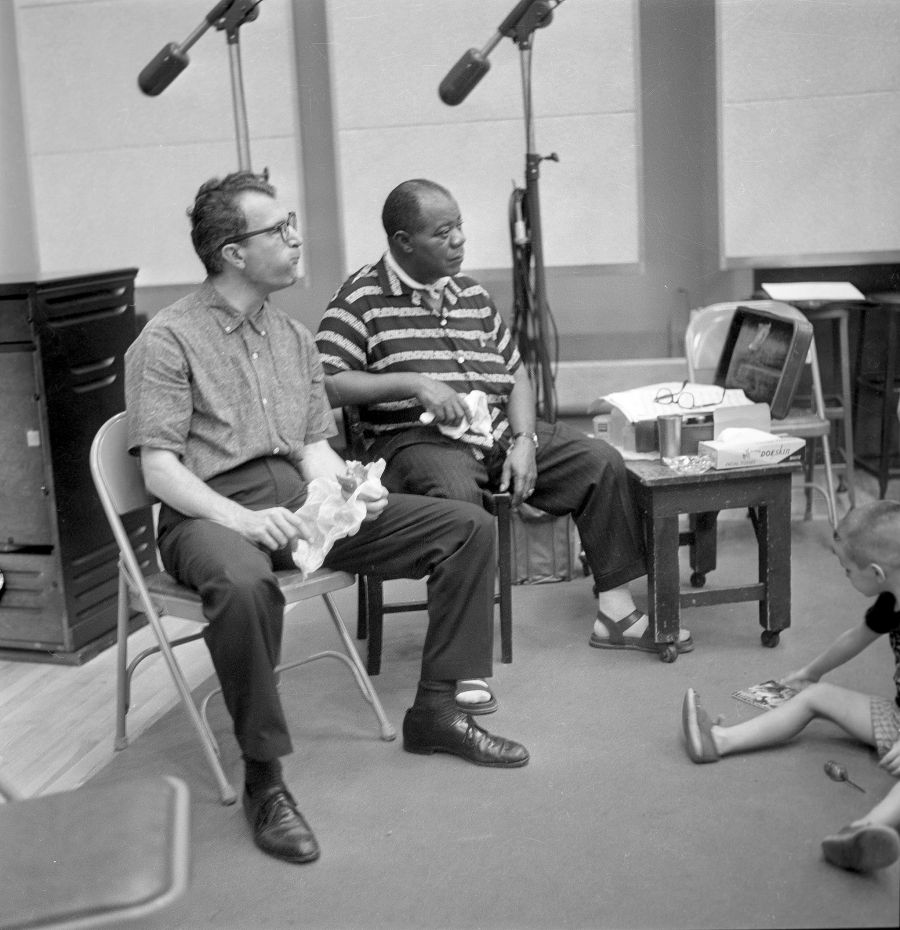

The Dave Brubeck Quartet in the studio (1959, Los Angeles)

Writing my book, as I researched his formative years spent in rural California, the son of cattleman Pete and piano teacher Bessie, Brubeck’s mature approach to the piano came into sharp focus. One of the myths that has simply refused to go away is that Brubeck was a classically-trained pianist who later ‘learnt’ how to play jazz, the uncharitable inference being that his feel for authentic jazz was once removed from the source and therefore overly schooled. This is not true. From all accounts, Bessie was a sensitive and thoughtful woman and she took music incredibly seriously. She enrolled on a course in San Francisco with the experimental composer Henry Cowell (whose music would later make such an impact on John Cage) and in 1926 travelled to London, leaving six-year-old Dave behind, to study with Tobias Matthay and Myra Hess.

Once back from London, she tried to teach her youngest son the rudiments of keyboard technique, but to no avail. Dave had already developed a taste for listening to jazz on the radio, which he enjoyed reproducing on the piano. He had become an ‘ear-player’ by instinct and by practical necessity – his reluctance to engage with music notation was also due to a diagnosis of the eye condition strabismus, which made peering at dots on staves a physically painful experience.

Dave Brubeck, Gerry Mulligan, Paul Desmond (1971, Boston)

Far from being classically trained, then, by his teens Brubeck had immersed himself in Art Tatum, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller, Count Basie and Benny Goodman’s pianist Teddy Wilson. He could play a mean blues and adored boogie-woogie: he rolled his left hand, eight to the bar, with the best of them. In my book, I argue that Brubeck’s visual impairment actually heightened his aural sensitivity and helped cultivate those bat-sharp ears. Because the sounds Brubeck heard on the radio had flowed through his imagination, and straight

down into his fingers, he gained ownership of them in a way unlikely had notation acted as an intermediary.

That persistent misnomer about Brubeck’s classical training has been perpetuated by what happened next. In 1946, having finally grappled with notation, he enrolled as a pupil of the great French composer Darius Milhaud at Mills College in Oakland – but as a composer, not as a pianist. The essentials of his piano style would come into being when Brubeck reconciled his deep appreciation of Ellington and Tatum et al with his studies of then modernist composers like Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Bartók and Milhaud.

Rhythmic shake-up

A bite of lunch with Louis Armstrong during The Real Ambassadors sessions (1961, New York)

Is ‘reconciled’ quite the right word? Another myth worth busting is that Brubeck’s ‘fusion’ of jazz with classical music pushed his work into a sterile middle-ground: in a now notorious review published in 1960, the influential jazz critic Ira Gitler haughtily dismissed Time Out as ‘drawing room music’ and ‘semi-jazz’. But Brubeck was never much interested in fusing anything. His instinct was to create musical structures inside which different styles, feels of time and harmonic moods could be heard to coexist – not blend.

Two Brubeck compositions from Time Out prove the point. ‘Blue Rondo à la Turk’ owes its existence to Brubeck hearing local musicians in Istanbul playing an infectious rhythmic earworm – 2+2+2+3 – which, it was explained to him, was the Turkish equivalent of the blues. A different musician might have figured that weaving a Turkish melodic line over the 12-bar blues form was an appropriate response to this discovery. Brubeck, though, worked up a structure in which a composed theme using the 2+2+2+3 rhythm was interrupted by choruses of the blues in a swinging 4/4 time. Not a fusion, then, more a mosaic – and again in ‘Three To Get Ready (And Four To Go)’ in which bars in 3/4, like a Haydn minuet, suddenly jump into delicately lilting bars of grooving 4/4.

The Brubeck Quartet’s experiments with time – Time Out would be followed by the albums Time Further Out, Time Changes, Countdown: Time in Outer Space, and Time In – swiftly became their calling card, whether playing ‘Some Day My Prince Will Come’ with 3/4 in the bass overlaid by 4/4 in the drums, or ‘Take Five’ in 5/4 and ‘Unsquare Dance’ in 7/4.

Researching A Life In Time, I had the thrill of listening to never-heard-in-public rehearsal tapes, recorded during the Time Out sessions in 1959, that reveal just how challenging the quartet found learning these new compositions. To make those tricky, asymmetrical rhythms line-up required coolheaded collective accuracy – and then the heat of improvisation required the opposite mindset altogether, as though the Brubeck Quartet needed to be the Juilliard String Quartet and a funky blues band all at once. Playing unorthodox time signatures quickly became second nature to the quartet and a later, less famous piece, ‘Unisphere’, recorded for the first time on Time Changes in 1964, demonstrates how nuanced their experiments had become – the group felt this piece in a genuine 10, not two lots of 5/4.

Order and chaos

With producer and broadcaster Willis Conover and jazz pianist Leonard Feather (1960)

One reason he never dabbled in drugs, Brubeck once explained, is that ‘you can’t play those complex rhythms if you’re stoned’, and his quartet acquired a saintly image as a well-oiled, well-mannered machine. But I also wanted to let the world know about Brubeck’s audacious improvisations, and the sheer excitement sparked when he wantonly torpedoed the formality of a composition with ecstatic improvisational revelry. This was Brubeck juggling the steely sense of order he had learnt from Milhaud – those lessons in harmony and counterpoint, and fugue – with the free-wheeling impulses of jazz.

For all the quartet had become famous for carefully executed compositions, they could also play entirely free.

In 1954, performing ‘Stardust’ at Berkeley College, they acknowledged only the barest outline of the theme, free associative chess moves overriding Hoagy Carmichael’s chord sequence. A year later, when the quartet recorded Richard Rodgers’ ‘Little Girl Blue’ on their album Jazz: Red Hot and Cool, Brubeck’s solo shifted from playing swinging jazz time over the chord changes to a sudden Jackson Pollock-like splatter of notes that defied conventional harmonic analysis; then his solo moved forwards by folding fragments of chords related to the tune around freely invented commentaries.

Twenty years later, ‘Truth’ traced a similar trajectory, order ripped apart by delirious chaos, and anyone whose experience of Brubeck begins and ends with ‘Take Five’ as it had appeared on Time Out is missing out on some truly great music. As a musician who had scored a huge (and lucrative) hit, Brubeck could have easily presented it as a polished and settled evergreen, but he baulked at the idea of playing routines and ‘Take Five’, live in concert, was constantly rethought and intricately dissected. An epic 16-minute version appeared on the same album as ‘Truth’, and Brubeck’s solo flooded the minor theme with major chords, before he cranked up the atonal tension.

As a 14-year-old I felt that Brubeck had handed me the code to some hitherto secret, undiscovered sounds. I began improvising at the piano, trying to unpick the sounds I’d heard. But when I demonstrated my newly discovered tone clusters and stocky discords to my piano teacher, after playing through my Grade 5 pieces, she looked me in the eye and said severely, ‘Sorry, those sounds don’t exist’. Through journalism, writing this book and playing improvised piano, I’ve spent the rest of my life proving her wrong.

Philip Clark's book, Dave Brubeck: A Life in Time, is available on Amazon.

Main image: Brubeck admiring a phrase coming from Paul Desmond’s horn (1961). ©The John Bolger Collection