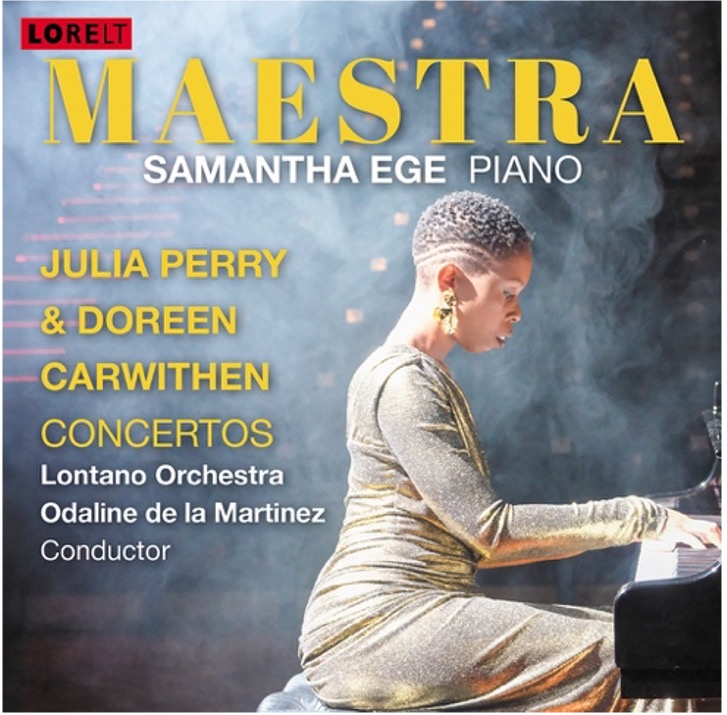

Samantha Ege talks to Pianist about her latest concertos recording – featuring works by Julia Perry and Doreen Carwithen – with the Lontano Orchestra and conductor Odaline de la Martinez, due for release on 25 March 2025 on the Lorelt label

Of all the large-scale compositions in classical music, the piano concerto is my favourite. I love how the piano takes the spotlight, commanding both sides of the stage: the listener on the one side, and the orchestra on the other. In the middle is the telepathic communication between the conductor and the soloist, reading each other’s thoughts, sensing each other’s breathing, absorbing each other’s gestures. There’s a magic to the concerto that is made even more spectacular when the unique textures and timbres of the piano are involved.

On my newest album, Maestra: Piano Concertos by Julia Perry and Doreen Carwithen, I make my contribution to this much revered genre. Under the baton of Maestra Odaline de la Martinez (the first woman to ever conduct a BBC Prom) and her orchestra Lontano, this recording sheds light on two brilliant women who shook up concerto with their compellingly eclectic sounds.

Julia Perry

Julia Perry was born in 1924 (two years earlier than Carwithen). She grew up in Akron, Ohio and studied music in some of the most prestigious spaces. From Juilliard to the private studios of Nadia Boulanger and Luigi Dallapiccola, Perry was at the heart of a dynamic musical era, known as modernism. The modernist sound broke away from the Romantic traditions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, which favoured tuneful melodies and conventional harmonies. A number of modernist composers, however, tore up the script, pushing tonality to breaking point.

Perry was at home with the modernists and her Concerto for Piano and Orchestra in Two Uninterrupted Speeds, completed in 1969, shows just how experimental she was. The concerto is a real celebration of her genius. She's not just writing musical notes; she builds a whole universe. The first speed (“Slow”) is, as Maestra Martinez calls it, “celestial.” Emerging out of a haze of strings and winds, the piano’s opening solo unfolds. The irregular time signatures evoke a sense of timelessness. But the second speed, “Fast,” brings us back down to earth. Energetic rhythms seasoned with lively syncopations dance around the pulse. Here, the piano cadenzas are more virtuosic (like Carwithen’s). But Perry is experimenting more with color than technique; the pianist must paint rather than play.

Doreen Carwithen

A contemporary of Perry’s, but from the other side of the pond, Doreen Carwithen was born in 1922 in Buckinghamshire. She studied at the Royal Academy of Music, where she soon formed a relationship with her professor, William Alwyn. By the 1960s, just as Perry’s career was taking off, Carwithen’s wound down as she gave up composition to dedicate her life to promoting Alwyn’s music. Signalling such a dramatic decision, she changed her name to Mary Alwyn.

The Concerto for Piano and Strings, composed in 1948, is a window into who Carwithen was before she became the more reserved Mary Alwyn. It is a cinematic work that anticipates her flair for film music. After all, she had led a pioneering career as a composer in the male-dominated movie industry. One of her most important assignments was scoring the music for a documentary on Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953.

Carwithen was a skilled musical storyteller, which shines through in this concerto. Each movement is infused with a narrative that captivates and inspires. Dramatic strings usher in the first movement, which is defined by an angular, yet muscular theme that follows in the piano part. A dreamy transition then introduces a lush, sentimental second theme. There is a constant tension between muscularity and sentimentality throughout. But in the second movement, the latter prevails. Yet, its color is significantly cooler, its mood more introspective. The violin renders heart-aching solos in dialogue with the piano’s pensive lyricism. The galvanizing rhythms of the last movement recall the relentless drive of the first. But leaving behind the tension of the opening movement, the closing cadenza breathes fire, passion, and catharsis into the concerto’s final moments.

Unlike Perry’s concerto, which was never performed in the composer’s lifetime, Carwithen’s concerto enjoyed, writes music historian Leah Broad, “an effusive reception after its broadcast premiere” in 1951 and a similarly enthusiastic response following its Proms premiere in 1952. For its Proms debut, the London Symphony Orchestra performed with conductor Trevor Harvey and pianist Iris Loveridge. 74 years on from its broadcast, it is with immense pride and pleasure that I bring Carwithen’s impassioned concerto to new audiences.

The wonderful thing about the piano concerto genre as a whole is that we, as listeners, get hear the composer’s voice in such mammoth form. But because, for so many centuries, society deemed women incapable of writing on such a scale (and often responded dismissively when they did!) we find there are fewer concertos by women to choose from. It’s not because they weren’t capable, it’s because the times in which they lived had a lot of catching up to do.

Luckily increased performances of concertos by historical women such as Florence Price, Clara Schumann, and Amy Beach are setting the record straight about women’s accomplishments in this genre of classical composition.

Samantha Ege's new album, Maestra, released on the Lorelt label

Maestra adds to the conversation. The album is a celebration of all that Perry and Carwithen accomplished in their restricted societies. It’s a celebration of Odaline de la Martinez’s legacy as a trailblazer. And it’s a celebration of one of the greatest instrumental genres: the piano concerto.

Even though Perry and Carwithen never met, I loved bringing their voices into conversation with one another for this album. At the height of their careers as composers, they had so much in common around their ambition and drive. Sadly, they sank into obscurity. Both Perry and Carwithen suffered strokes towards the ends of their lives. Perry passed away in 1979, and Carwithen in 2003. But with Maestra, they shine so brightly together.

Main image of Samantha Ege: © Jason Dodd