Forget cartoons and recordings, says Lucy Parham, and tune your ears to the bells of old Russia in Rachmaninov’s early masterpiece

Don't have the score? You can download the full piece from our Scores store, here.

The most famous piano piece ever written? So some have said. Rachmaninov felt he was cursed by this piece in later years because he said it was all that people wanted him to play. He reached a point where he no longer wanted to perform the Prelude and he simply ‘detested’ it: ‘I have heard my inescapable Prelude played superbly by many professional pianists and cruelly murdered by many amateurs, but I have never heard it played as well as by the great Maestro Mouse in the Walt Disney film, Mickey’s Opry House.’

While we're struggling to find a recording of Mickey Mouse playing the piece (!), we did find a stunning performance from Evgeny Kissin. We hope you enjoy it just as much.

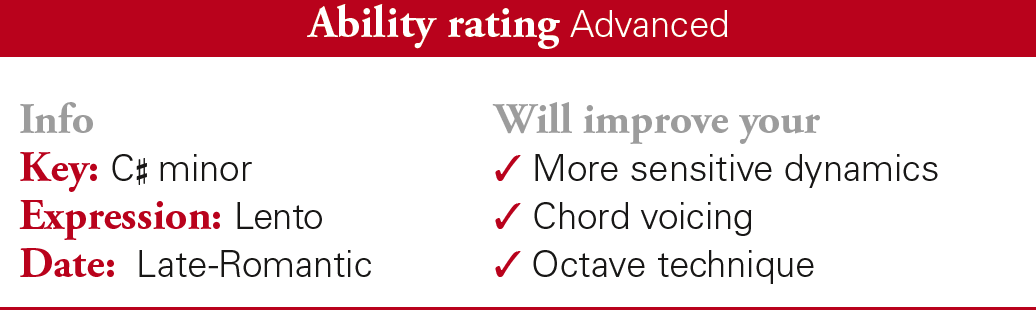

Don’t let the fame of this piece put you off. It is a masterpiece in symphonic piano writing and it tests the pianist in many ways. Firstly, the dynamics range from ppp to ffff, so finesse in terms of managing your levels of sound is required. Also, the central Agitato section (the triplet figuration) is technically quite challenging – especially in the final flourish cadenza.

Rachmaninov loved the sound of bells all his life. As a child, he was often taken to church by his maternal grandmother in the city of Novgorod. He commented that hearing these bells throughout his childhood had influenced many of his compositions, from large-scale orchestral works through to solo piano pieces. Indeed, this Prelude is steeped in bell sonorities. The more you think about the ffff climax the more you can hear the bells pealing in glorious unison. Awareness of this will lend power and context to your performance.

TIP 1: The lengthy notes in the opening should resonate like a bell

So, to the start of this great piece. This opening is so famous that it can be difficult to play it exactly as it is written and not just as you have heard it in many recordings. One of the main problems comes in bar 2, on this long semibreve C#. This note should be held for the full four crotchet beats. You will seldom hear it done like that, possibly because in performance it can seem like a very long time to hold a single note! I find it easier to subdivide the note and count it in quavers, as it is the quaver beat that propels the melody which is to follow.

The opening four bars

Don’t overlook the preceding two crotchets of A and G#. They complete this opening statement which is full of darkness and melancholy. Draw each of these crotchets out of the keyboard with big, whole-arm movements.

Imagine the entire brass section of an orchestra playing these opening notes – listening to Leopold Stokowski’s opulent orchestration of the Prelude below may give you some ideas.

However the fortissimo dynamic should not lead you to hit the keys or give rise to an aggressive interpretation. The Prelude has an underlying sense of nobility and grandeur: it shouldn’t sound tight or forced.

The long C# in bar 2 will naturally decrease in volume like the resonance of a bell. Don’t rush past this resonance. At the end of the bar, observe the level of dynamic you have reached and use that as a starting point for the next bar. This will match the sound you make from phrase to phrase, so that the next bar emerges from the depths of the long C#.

In bar 3 the melody begins. Voice these chords carefully, with plenty of top finger in the RH, a clear but not dominant bass line and each of the inner parts distinct. This is easier said than done! When practising these chords try omitting the 5th fingers in both hands, then play only straight octaves, with no inner parts. This will help to make you aware of the direction of each individual line.

TIP 2: Take extra care over the accent and staccato markings on the opening page

Note the dynamics on the first page. There should be a noticeable distinction between the ppp dynamic at the start of the melody and the mf in bar 7. A true ppp requires fine control of the fingertips; the practice technique outlined above should help. At bar 9, the ppp returns, now subito (without a preceding diminuendo), so make sure you go back to this hushed, veiled sound. Imagine the melody coming from afar.

The staccato lower octaves could be gently drawn out of the keyboard, whereas the following accent might benefit from you leaning into the note. Then in bar 13 the melody descends into the depths of the keyboard. The role of the LH is especially important here as by voicing this carefully you can achieve more prominence in the lowest level.

Bars 13-14

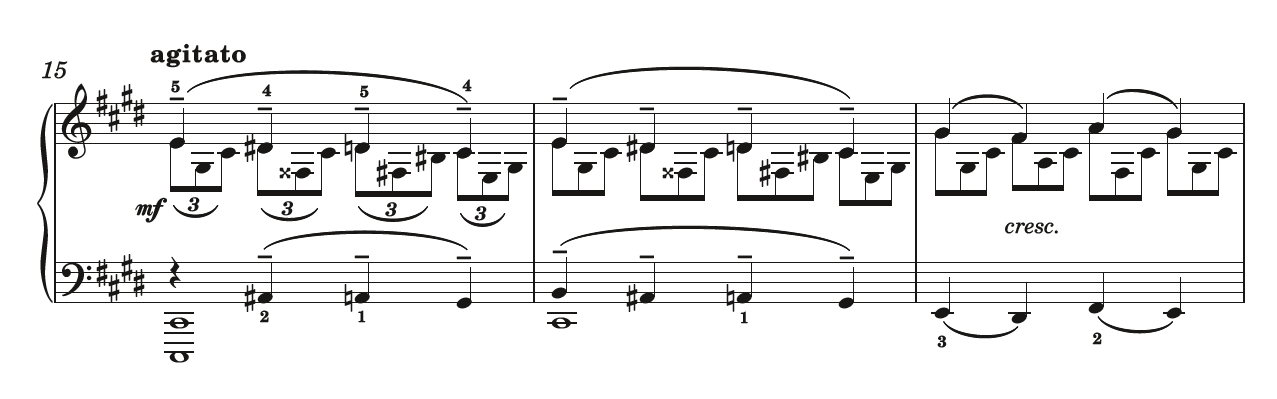

TIP 3: Remember – agitato, not presto

A new, more technically demanding Agitato section of the piece begins at bar 15. Resist the temptation to play this too fast as agitato does not mean presto, and you need to reserve some momentum for later on. The tolling bell-chords are now surrounded by a triplet figuration. The prevailing unease of this figuration is what the Agitato marking refers to. I suggest practising this section without the triplets to begin with. This strategy will help you to hold the LH and RH melody (which almost forms a duet at the start) in balance.

Bars 15-17

The four descending notes in the melody evoke pathos and pleading. Think of them as a long, four-note slur. Note the crescendo and diminuendo from bars 17 to 18 and then again (although reversed) in bars 25 and 26. The Agitato section should not come to the boil too quickly. When you do reach the climax of this section at bar 36, don’t be tempted to hang back: drive forward and keep drawing more and more tone out of the keyboard so that the climax really booms out of the piano. Keep your wrists firm and observe the accents as that will help to keep the rhythmic structure. The small commas in the score show you where to breathe and phrase. Note the sfff markings in bars 44 and 45 and give this your last ounce of energy!

TIP 4: Practise bars 46 onwards hands separately in order to master the leaps

The principal climax of the piece arrives at bar 46. This is marked pesante (heavy) and the weight of these chords is paramount. It is as if a carillon of bells is chiming all at once, and to evoke this will require considerable arm and shoulder weight. If you have learnt this part first, it should sit more comfortably under the hand. Tracing the octaves with your thumbs should help the hand displacement. Take time to practise this section with hands separately in order to master the leaps. The climactic chord is the third quaver of bar 53.

Bars 52-54

It is like a final, desperate plea. Everything thereafter should gradually subside. Focus the tone on the 5th finger of the RH at bar 54 and the first half of bar 55.

Make a smooth diminuendo through the last eight bars. The theme of bells is ever-present, so while it is important to highlight the inner notes in the RH (played with the 2nd or 3rd finger), the top C# notes also require a steely 5th finger. The bass C# and the top C# should be connected in your mind, the treble as an echo of the bass. These eight bars become progressively quieter, but don’t lose tone too soon: the diminuendo begins from a fairly quiet point. Leave the pedal and listen to the sound evaporate as you release it gently to return to the silence from which the Prelude first emerged.

This article is taken from Pianist 103, available here.